How gut bacteria can boost cancer immunotherapy efficacy?

Researchers looked into how gut bacteria affected mice’s response to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy. They discovered that ICIs enable specific gut bacteria to get through tumor locations. It then stimulates the immune system, which then destroys cancer cells.

To confirm whether these results may apply to humans, more research is required.

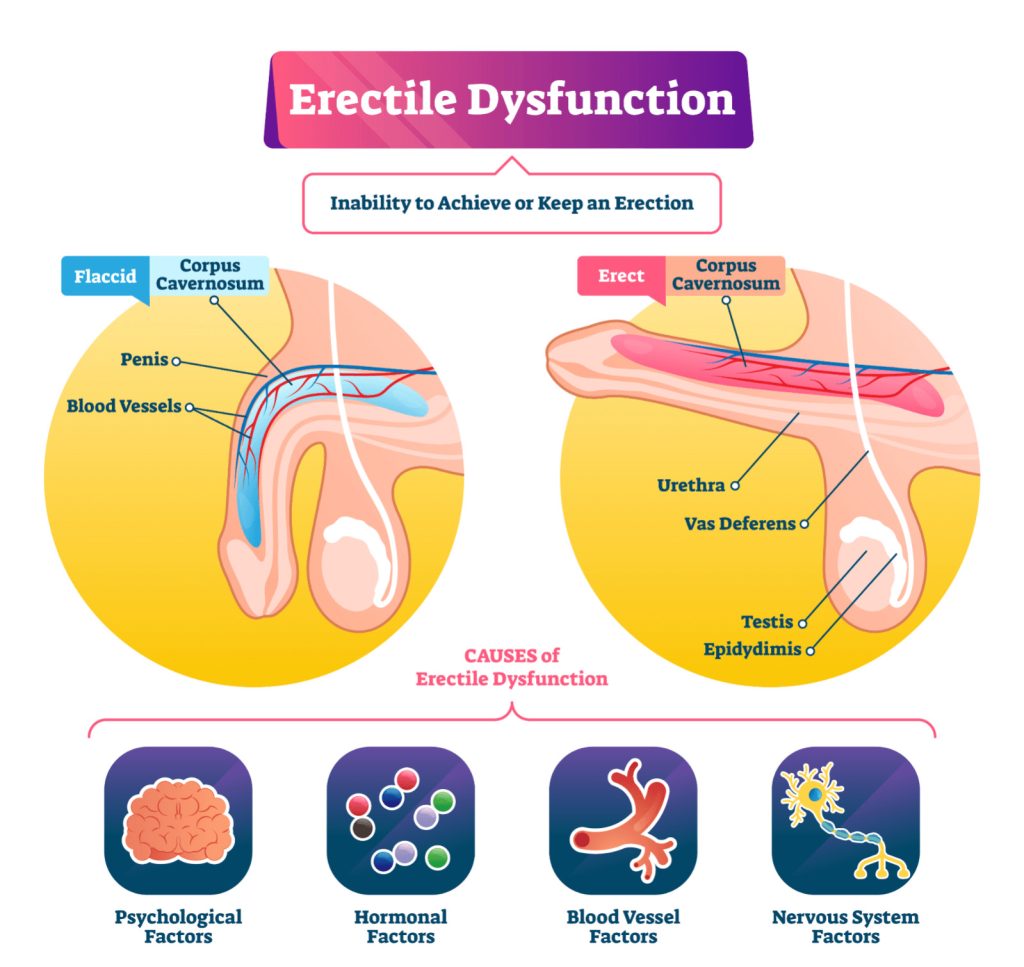

Immunotherapy includes the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). They function by “taking the brakes off” of the immune system so it can eliminate cancer cells by blocking certain proteins that restrict immune function, such as CTLA-4 or PD-1.

Unfortunately, ICI therapies are ineffective in up to 50% of cancer patients. The effectiveness of ICI treatment may be influenced by the gut flora, according to a growing body of research.

According to research, animals with impaired gut flora or those given antibiotic treatment react to ICI less favourably. Studies have also shown that faecal transplants of new microbiota may improve ICI responsiveness.

The best gut bacteria for boosting ICI response and the mechanism by which gut bacteria enhance immune response are still unknown.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors(ICI) and gut bacteria

Recent studies examined the relationship between gut bacterial diversity and ICI effectiveness in a mouse model of melanoma.

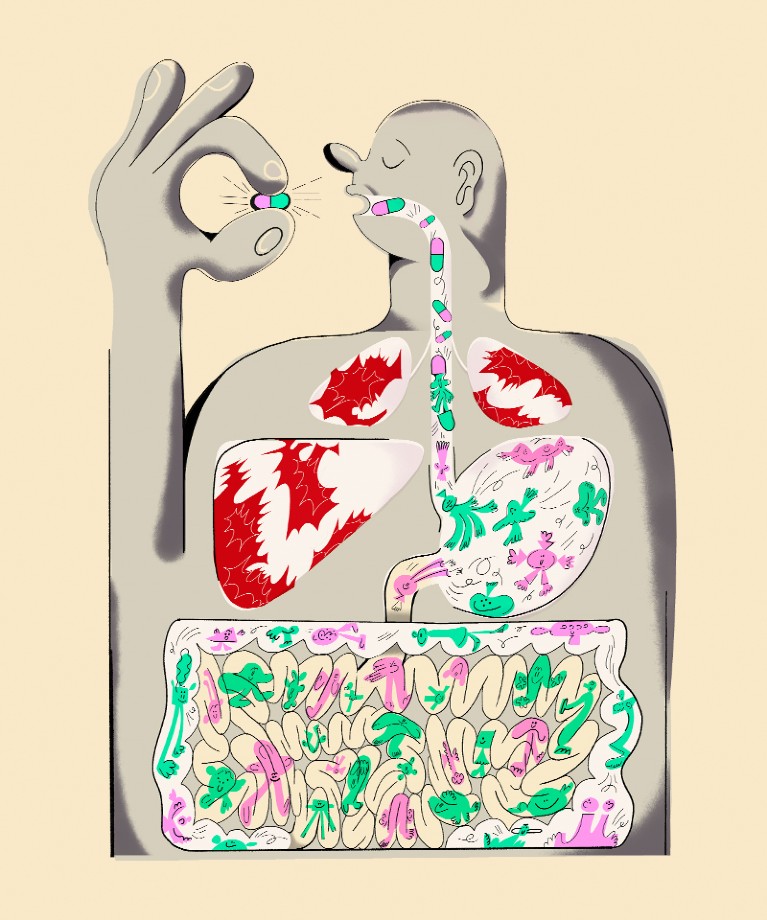

They discovered that ICI treatment results in gastrointestinal inflammation. This allows bacteria to get through the intestines. Thereby moves to lymph nodes close to tumors where they activate immune cells.

The research is published in Science Immunology. Even though checkpoint inhibitor treatment has demonstrated unheard-of clinical success, a sizable portion of responders will later develop acquired resistance. As previously mentioned, the gut microbiota has a significant impact on host anti-tumor immunity in several ways. This affects the clinical reactions and outcomes of cancer immunotherapy patients.

Dr. Anton Bilchik, chief of medicine and director of the Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Program at Saint John’s Cancer Institute in Santa Monica, California, as well as a surgical oncologist and division chair of general surgery at Providence Saint John’s Health Center, did not take part in the study.

Investigating ICI efficacy

Mice with and without melanoma tumours received ICI therapy as part of the study.

They discovered that ICI treatment exacerbated gastrointestinal inflammation, allowing certain bacteria to pass from the gut to lymph nodes close to the tumour as well as the tumour site. In that location, the bacteria triggered a group of immune cells that destroyed tumour cells.

The effectiveness of ICI may be impacted by antibiotic exposure, according to the study. To do this, mice were first given antibiotic treatment. Further followed by melanoma tumor implantation and ICI treatment a week later.

They discovered that exposure to antibiotics lowered the number of immune cells and the migration of the gut microbiota to the lymph nodes.

Finally, they looked at whether giving out certain bacteria may counteract the effect of the antibiotics on the effectiveness of the ICI. They discovered that using Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecalis in treatments increased ICI effectiveness.

Fecal microbiome transplantation

FMT is the most direct way to change the microbiota. Feces from one donor is given to another by lyophilized or frozen pills that are taken orally. Also, they can be delivered directly via colonoscopy or gastroscopy.

With almost 300 registered clinical trials as of now, FMTs are being investigated as a treatment alternative for an increasing range of illnesses (clinicaltrials.gov, accessed Aug 2021). Over the past ten years, it has been clear that FMTs are extraordinarily effective at treating resistant and recurring Clostridium difficile infections. This helps patients feel better and get rid of their clinical symptoms.

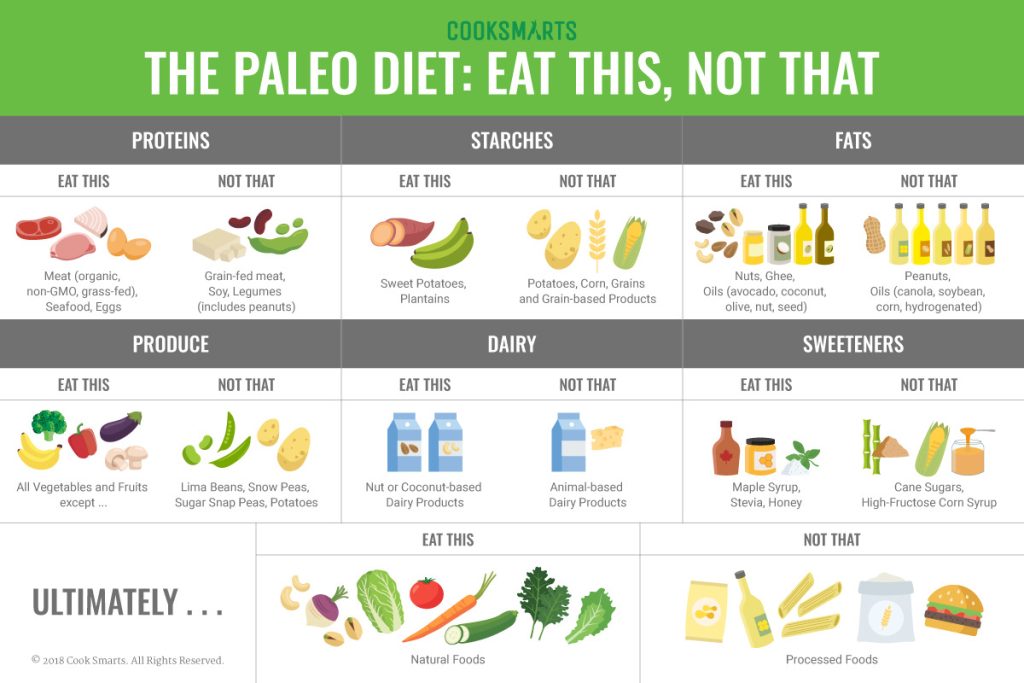

Dietary intervention and lifestyle

The relationship between diet and the microbiota has been studied for numerous years at various resolution levels because gut microbes have a role in food digestion. In fact, distinct microbial communities are closely involved in the sequential host digestion and nutrient extraction, with the gut microbiota playing the major role.

On the one hand, the host’s inability to digest a large number of chemicals released by the gut microbiota affects the food’s ability to provide nutrients. Contrarily, both short- and long-term dietary modifications can affect the microbial transcriptome and metabolomic profiles, especially for newborn nutrition. This may have long-term effects through microbial modulation of the immune system. For instance, high-fat diets are linked to significant changes in the makeup of the colonic microbiota. This includes decreases in both Gram-positive.

Study restrictions

Dr. Andrew Koh, senior author of the present work and associate professor at the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center at UT Southwestern, was contacted by MNT to discuss its limitations.

They only employed one preclinical cancer model, which, according to Dr. Koh, is a significant restriction, necessitating additional research to see whether the results also apply to other cancers.

Although we have not yet produced evidence to support that notion, we think that our findings may also be applicable to other tumours, he said.

According to published research, various human cancers include specific or unique tumour microbiomes, and many of the prominent taxa are bacteria that normally live in the gut. Dr. Bilchik stated that it is still unclear whether the results apply to people when asked about the study’s other limitations.

Interventional gastroenterologist Dr. Lance Uradomo, who is not affiliated with the study and practice in Irvine, California at the City of Hope Orange County Lennar Foundation Cancer Center, stated that “the type of therapy applied for testing melanoma can be linked to adverse side effects, such as colitis.”

Before it is known if microbiome therapy — and the proper administration — is genuinely successful, more research is required, he continued.

Conclusion

The gut microbiome appears to have a significant impact on host immunity and therapeutic response in cancer, either locally within the tumour microenvironment or via systemic antiviral immune responses, according to strong evidence from preclinical and clinical research. The latter is most likely the reason why the gut microbiota is able to control how the body reacts to immunotherapy and traditional chemotherapeutic drugs, eventually having a variety of effects on patient outcomes.

REFERENCES:

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/how-gut-bacteria-can-boost-cancer-immunotherapy-efficacy

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/ebiom/article/PIIS2352-3964(22)00344-9/fulltext

- https://gut.bmj.com/content/69/10/1867

For more details, kindly visit below.